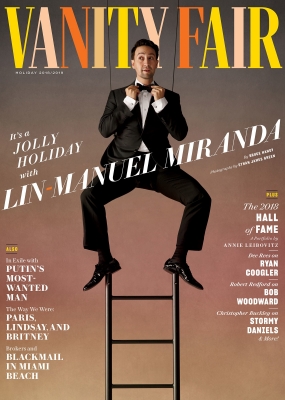

Lin-Manuel Miranda is on the cover of Vanity Fair’s Holiday issue, with a beautiful photoshoot and a long article.

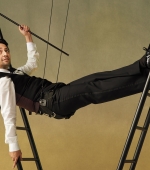

Check the photos in HQ in our Gallery! [Edit: Added a photo report shared by Vanity Fair shot when Miranda took part in the Families Belong Together March in Washington D.C.]

Also, they have Lin-Manuel explain you Broadway slang in a video! [EDIT: Added a behind the scene video from the photoshoot.]

The piece starts describing the first image of Mary Poppins Returns, that is all about Miranda apparently.

The first image you see in Mary Poppins Returns is a gas flame dancing in an old-fashioned street lamp, just before dawn. It’s an apt way to start the movie, which, more than half a century later, means to rekindle the spirit of Walt Disney’s 1964 adaptation of the P. L. Travers children’s books. Some would argue (well, I would) that the original Mary Poppins is the greatest of Walt Disney pictures—Disney, the actual man and studio head—so that crafting a sequel is a Herculean and possibly foolish task. Blame or salute director Rob Marshall (Chicago, Into the Woods), screenwriter David Magee (Life of Pi), and songwriters Marc Shaiman and Scott Wittman (Hairspray). But here we are.

The second thing you see in Mary Poppins Returns is a close-up of Lin-Manuel Miranda, tending the flame literally and figuratively as a Cockney lamplighter named Jack. Those of us happy just to have had tickets in the rear balcony when we saw Hamilton, the epochal hip-hop musical Miranda wrote and starred in on Broadway, or In the Heights, his first show and the rare Broadway hit with Latin music actually written by Latinos, may not have realized how expressive his big brown eyes are, especially on a movie screen. Here, with his face shorn of its customary beard and mustache, those eyes, no longer counterbalanced by whiskers, look almost ridiculously, Keane-ian large. They’ve been unleashed, like a pair of excited puppies—adorable and up for anything. In tandem with the gaslight, they seem meant to welcome us into the magical, innocent, sentimental world of Mary Poppins Returns, and they give us the first hint that this thing might work.

Read the rest of the article under the cut.

You no doubt remember Bert, Dick Van Dyke’s chimney sweep and one-man band, from the original; Miranda’s Jack serves much the same purpose here, as both a scene-setter and a sidekick to Mary Poppins herself. Indeed, we are told that Jack was once apprenticed to Bert as a boy, back around the time of the first movie. The new one picks up with the Banks family 25 or so years later, in the pre-war 30s, with London gripped by the Great Slump, as Brits style the Depression—Marshall’s Mary Poppins living in a world just a shade darker than Uncle Walt’s. Bert himself is no longer in evidence, having presumably passed on to one of those clouds we first saw Mary perched on more than 50 years ago. Mr. and Mrs. Banks have also left us. Every other principal from the first movie has aged appropriately: Michael Banks (Ben Whishaw) is now a widowed father of three. Jane Banks (Emily Mortimer) is a union organizer and devoted aunt. But Mary herself is unchanged and eternally youthful, except that she now looks like Emily Blunt rather than Julie Andrews, and owns a slightly snappier wardrobe. There is a functional plot, having to do with an evil banker (Colin Firth) who means to repossess 17 Cherry Tree Lane, the Banks’s homestead, and parental challenges requiring magic-nanny intervention. But what will matter more is that there are new songs, a few tears, and a goofy cameo by Meryl Streep; there is Blunt inhabiting the role with all due banister-ascending mischief and spit-spot persnicketiness; and there is Lin-Manuel Miranda, who looks like he is having a blast, which is largely what his character is asked to do. (I choose to interpret his wobbly Cockney accent as a tribute to Dick Van Dyke’s famously unconvincing stab at same.)

Rob Marshall and John DeLuca, Marshall’s producing partner as well as his partner partner, cast Miranda after seeing him in Hamilton, consciously following the template set by Walt Disney, who gave Andrews her first big-screen role in Mary Poppins after she had become a Broadway star in My Fair Lady and Camelot. “We were blown away by the spirit behind Lin’s work as an actor—there’s an unusual purity to it,” Marshall told me. “What’s so fascinating about getting to know Lin personally is that there’s not a jaded bone in his body, and we were looking for Jack to have an optimism, a child-like sensibility. Lin just has that ‘it’ thing, and it comes right through the lens.”

Not a jaded bone in his body. Sam Wasson, a friend of Miranda’s from their undergraduate days at Wesleyan, said much the same thing when he described Miranda as “a human gumdrop.” At Wesleyan, Wasson and Miranda worked on shows together, including an improv group that Miranda played music for. “He was game for anything,” Wasson said. “He had a little Mickey-and-Judy feeling in him. ‘Let’s go! Let’s do it!’ It’d be impossible to think of Lin as depressed in any way, which makes me hate him. You want to think, ‘Oh, genius comes with darkness,’ and I’m sure it’s there, but I haven’t seen it.”

Another word that comes up repeatedly while talking to Miranda’s friends and colleagues is “ebullient.” It’s a quality that’s palpable not just in his persona and his performances; it also animates his relentlessly upbeat Twitter feed as he bounces between sharing cute videos of his kids and showering his 2.53 million followers with daily affirmations. (“Good morning! Give your time, give your heart, give your talent, give something new. It feels incredible.”) More importantly, that positivity courses through the shows that made Miranda’s name. There was an electric cultural synergy when Hamilton debuted in 2015 with Barack Obama in the White House: Miranda’s book, score, and cast implicitly conflated the revolutionary energies of a young nation with those of our multicultural moment. But Hamilton’s opening night on Broadway was August 6, just weeks after Donald Trump announced he was running for president. As in Mary Poppins’s London, things have changed, and lights in the darkness must now burn brighter than ever.

“Mary doesn’t age, right? Which makes her kind of like a Time Lord.” That was Miranda one afternoon this summer, explaining the ground rules of what I hope no one at Disney refers to as the Poppinsverse. “Time Lord” (I had to look it up) is a reference to Doctor Who and that series’s race of time-bending aliens who can also regenerate themselves whenever plot twists or casting changes demand. You can imagine the novel appeal of characters who have literally all the time in the world to someone whose signature work is about a man haunted by the specter of an early death; as Miranda’s Eliza Hamilton sings to her husband, “Why do you write like you’re running out of time?” It’s a refrain that underscores Miranda’s own life and work, well beyond Hamilton.

“If you look at In the Heights, it’s also a show about legacy and what you leave behind. That’s in the fabric of a lot of the things that Lin makes, that and asking the question, ‘Have I done enough?’” said Thomas Kail, who directed In the Heights as well as Hamilton. “Lin has a real understanding of how fleeting everything is. The only time you ever really see Lin scared is if you ask him to cross the street not at a crosswalk. He’s conscious that things could end and he’s conscious of the randomness of things. So he tries to impose some kind of order within that chaos.”

You and I might well think that, yes, Miranda has done enough, given that he’s only 38 and already has a Pulitzer Prize, a MacArthur genius grant, an armful of Tonys and Grammys, and an Emmy, leaving him just an Oscar short of an EGOT. (He earned a nomination in 2017 for best original song for “How Far I’ll Go,” one of his contributions to the Moana score.) Then again, you and I are probably not the sort of people who would read an 818-page biography of a Founding Father while on vacation in Mexico, and say to ourselves, while floating on a lounger, “This needs to be a hip-hop musical!” (Or so goes the Hamilton origin story.)

Consider the rush of Miranda-related events this past summer—which a friend of his likened to “a Lin-Manuel Miranda Advent calendar.” In late June, Warner Bros. announced that it would be releasing a movie version of In the Heights in 2020, to be directed by Jon M. Chu, now among the most bankable filmmakers in Hollywood thanks to Crazy Rich Asians. Then, in short succession across July, it was announced that Miranda would himself be directing a film adaptation of Tick, Tick . . . Boom!, the Jonathan Larson musical that isn’t Rent; that Miranda would executive-produce a limited series for FX based on a biography of the director and choreographer Bob Fosse (with Sam Rockwell as Fosse and Michelle Williams as the dancer Gwen Verdon, Fosse’s wife and muse); that he would be co-starring in a BBC adaptation of Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials trilogy; that Penguin Random House would publish an illustrated collection of his most uplifting, go-get-’em tweets; that he had started a multi-million-dollar fund to promote the arts in Puerto Rico in the wake of Hurricane Maria; and that all the profits from a previously announced three-week San Juan production of Hamilton, which Miranda will be starring in come January (reprising the title role for the first time since he left the Broadway production in 2016), will go to benefit the arts fund. This last announcement was made at a press conference in Puerto Rico, where both Miranda’s parents are from, and where he spent considerable time as a boy while growing up in New York City.

Pity the fans—not to mention the journalists—who have to keep up with all this. I interviewed Miranda in New York a few days after the press conference. His public schedule began that morning at 7:20 with him tweeting a video he’d taken of himself in a subway station performing a discarded rap from Bring It On: The Musical, the 2012 Broadway cheerleading show (based on the film franchise), for which he’d co-written the music and lyrics. Even bigger news came a few hours later: the committee behind the Kennedy Center Honors was bestowing an “unprecedented” special award to Hamilton—the first time the center had honored a specific work as opposed to artists or performers with extensive bodies of work. Thus, this month, Miranda, Kail, musical director Alex Lacamoire, and choreographer Andy Blankenbuehler will be fêted at the Kennedy Center’s annual gala alongside Philip Glass, Reba McEntire, Wayne Shorter, and Cher.

Cher! Of course Miranda has a Cher story: she saw him in Hamilton but didn’t come backstage because, as she explained in a subsequent note, her tears had ruined her makeup—which might be Miranda’s most unlikely feat of all, making Cher feel shy. He and I met in the apartment he rents as a workspace and hangout in Washington Heights. (People assume, per the title of his first show, that Miranda grew up in the Heights, in northern Manhattan, but his family actually lived 30 blocks further uptown, in Inwood.) This apartment is not far from the one where he lives with his wife, Vanessa Nadal, a chemist turned lawyer, and their two young sons, a four-year-old and a baby who was born this past February—a few hours after Miranda and Nadal saw an early cut of Mary Poppins Returns. (As he put it: “If you ask me, ‘How’s the movie?,’ I go, ‘It is labor-inducingly good!’”)

He’d only just arrived in town that morning on a red-eye from Los Angeles, where he’d flown from Puerto Rico for two days of work and meetings, but he showed no signs of jet lag. Sort of the opposite, in fact: he was full of energy, nervous or otherwise, and couldn’t stop bouncing all over his chair, straddling the arms at times or perching on the back. At one point he sprawled on the floor to show me how the camera had been placed for a tricky motorized shot in one of Mary Poppins Returns’s numbers. You could see why he had been drawn to performing in the first place. It was almost as if being asked to sit in one place for two hours was a physical affront.

That impression was confirmed by Quiara Alegría Hudes, the Pulitzer-winning playwright for Water by the Spoonful, who wrote the book for In the Heights. Once or twice during previews for that show Miranda was forced to let an understudy take over his role so he could sit in the audience with Hudes and, as she said, “put his author hat back on for some things we needed to fix. And I remember one time he turned to me and he just looked miserable, which is not something Lin looks very often—he is an incredibly happy human being. But he looked dreadful, just ashen in the face, and I was like, ‘What’s wrong?’ And he was like, ‘How do you do this? How do you sit and watch every night? It’s the worst experience. It’s awful! There’s nothing I can do with my nervous energy!’”

It is tribute to both his creative intensity and the frenzy generated by Hamilton’s success that Miranda can make taking on his first major movie sound like an escape, never mind that Mary Poppins Returns represents an enormous creative risk for all concerned. Marshall and DeLuca offered him the part while he was nearing the end of his one-year commitment to his Hamilton role. “A year,” he said, “that’s like when my warranty runs out, so this really was a weird kind of a lifeline. It was getting a bit crazy, the celebrity thing about Hamilton here in New York, and to chop my hair off and leave the country was a very enticing prospect.” The offer helped at home, too: “The other thing you have to know is my wife is Dominican and Austrian. She was born in Sweden and wants to live everywhere in the world. My first musical is literally about how I do not want to leave Washington Heights.” Thus, the prospect of spending a year working in London and submitting himself to someone else’s vision for a change held the bonus appeal of resolving his Green Acres-style conflict—though Nadal told me she thought her husband was perhaps exaggerating for effect regarding that last point, and also regarding his relief at being offered the role and his eagerness to skip town. “I think he’s underselling himself a little bit,” she said. “He would have also been happy to stay in New York and he would have figured out” his next career move. “But it had been an exhausting year. We would have to take a very long vacation.” When I asked if Miranda ever gets depressed or mopey or just vaguely “down” in private, she replied—following a deliberative pause—”I will say that the public perception is not very far off the truth. He has a very positive attitude almost all the time.” She then told me a story about how, when he learned Beyoncé and Jay-Z were coming to see Hamilton, Miranda had vowed to perform that day even though he had a 104-degree fever. “He was like, ‘Maybe I can do it.’ And I was like, ‘You can’t do it. You’re crazy.’” Nadal won that argument.

As a kid, Miranda had a complicated relationship with Mary Poppins. He still remembers the VHS case fondly, but the movie itself gave him pause. “I couldn’t get through ‘Feed the Birds,’” he admitted, referring to the gorgeous, melancholy lullaby Andrews sings halfway through the movie, about an old woman in rags who sells birdseed on the steps of St. Paul’s—the kind of glum note the new movie amplifies just a bit. “I was very sensitive to minor-key music, and that song was so sad that I don’t think I saw the ending of Mary Poppins until I was grown, because I would just cry. I loved ‘Supercalifragilisticexpialidocious.’ I loved Dick Van Dyke. I loved the whole movie but then that one song was so sad I kind of never survived it.”

Having a strong emotional response to music at a young age is often cited as evidence that a child has a musical gift; a friend of mine’s kindergarten-age son was accepted to a program for piano prodigies in part because he wept listening to Chopin. I asked if Miranda had often responded to songs so passionately as a kid, and he practically jumped out of his chair. “My family had so many stories about that, about how Stevie Wonder’s ‘I Just Called to Say I Love You’ would come on and they’d have to change the channel because I would burst into tears. You know what? I actually remember the feeling. I remember it was so many ‘nos’ in the lyrics. ‘No New Year’s Day to celebrate’—it felt apocalyptic to me as a little kid. ‘No songs to sing’—I was like, ‘Turn it off!’ I was very sensitive. ‘Bridge Over Troubled Water’ apparently just laid me out when I was an infant. My parents have all kinds of stories like that.”

His parents’ record collection is a big part of Miranda’s own origin story, the show tunes from Broadway cast albums they’d relax to and the salsa and merengue they’d play at dance parties, both strains entwining to form his musical DNA, along with the hip-hop he absorbed as a kid, which served as a kind of accelerant. Another key influence: seeing Rent on his 17th birthday. “Jonathan Larson connected the dots in musicals—that this thing you love can reflect the world in which you live. I loved musicals. But they never reflected the world in which I lived. It was just a separate thing I liked. He connected those dots for me, and I think I really started writing and felt like I could write a musical because of Jonathan Larson.”

Which makes Miranda’s directing a movie version of Tick, Tick . . . Boom! a form of debt service. Larson’s autobiographical show, its earliest version first performed Off Off Broadway in 1990, centers on a marginally successful musical-theater composer who is contemplating giving it up as his 30th birthday looms. The stage production opened to the literal sound of a ticking clock. The show has a happy ending, but it’s impossible not to view it through the bitter lens of Larson’s shocking death, in 1996, from an aortic aneurysm, at the age of 35, the morning of Rent’s first Off Broadway performance—which is about as cruelly ironic as death gets in real life. (Rent, of course, is stalked by death, too, in the form of H.I.V./AIDS.)

“Everything’s been preparing me to direct Tick, Tick . . . Boom!,” Miranda continued, “both from my upbringing with Jonathan Larson’s music and from my understanding of what it’s like to be a struggling composer in your 20s trying to get your show on and trying to get a different vocabulary heard—trying to get Broadway to sound more like the world you actually live in. Which was Jonathan’s whole quest, and he succeeded in spades and he didn’t get to see that success. But for me, what I love most about Tick, Tick . . . Boom! is it’s not about Jonathan Larson’s death at all. It’s really about his struggle, about coming to New York and being the one who still bangs your head against the wall while your friends have gone into, maybe, cushier jobs or diverted their dreams into finding something else they love to do. We all have our version of that.”

In a 2015 New Yorker profile of Miranda that ran just as Hamilton premiered at the Public Theater, Rebecca Mead wrote that “during rehearsals for the Broadway run of Heights, Miranda developed the superstition that he would die before opening night.” As he told Mead, “It was like a running joke: ‘Unknown Composer Falls Down Manhole.’ ‘Unknown Composer Hit by Bus.’” I raised this with him, and the obvious connection to Larson’s life, work, and death, and to Miranda’s doomed Alexander Hamilton.

“And Bob Fosse’s got the ticking clock, too,” he pointed out, bringing up his pending FX series. Indeed, Fosse’s 1979 quasi-autobiographical movie musical, All That Jazz, ends with an audacious, spectacularly bizarre, 10-minute number about the Fosse character’s fatal heart attack, “Bye Bye Life” (to the tune of the Everly Brothers’ “Bye Bye Love”).

“Fosse, Larson, Hamilton—they’ve all got this awareness of the ticking clock,” Miranda continued, “and I think I very much have that, the awareness of ‘All right, this is how much time we have. How much can we get done while we’re here?’”

I asked whether that urgency had been fostered by his teenage connection to Larson’s work, or whether it was something he’d felt his whole life. “Well, I think the tragedy that Larson did not get to see his own legacy resonated with me enormously. But, it was his worth that I really responded to—more than his passing. I felt so seen by the character of Mark in Rent when I first saw it—the guy who just films everything because he doesn’t really want to engage. That’s what I was like in high school. I had a big-ass camcorder and I would film all my friends when they were hanging out. I literally have footage of my friends eating snacks and being like, ‘Why are you filming?’ Because it was easier for me than sitting and hanging out! I don’t know what hanging out is.” He added—for what it’s worth—“I’ve relaxed a lot more since I was a teenager.” But most teenagers and people in their early 20s are fairly heedless about risk and death—famously, often tragically so. What, I pressed, fueled his rare sense of urgency?

He paused for just a moment, then said, matter-of-factly, “I had a close friend who passed away when I was about three years old. That’s among my earlier memories. It was a kid who was in my class, in my pre-K. It was one of those tragic things.”

I asked if he minded explaining what had happened. “It’s really sort of not my story to tell,” he replied, “but she drowned. It was just one of those horrible stories where no one had an eye on her in a critical moment and that happened. No one’s fault. It’s just what happened.”

He said all this with a subdued evenness in his voice. But then his switch turned on again: “There’s an extraordinary moment in the Harry Potter books. It’s like the fifth book, where Harry gets into the carriage to take them all to Hogwarts Castle and he sees these giant invisible horses. And no one else sees them. He’s like, ‘What are those?’ And only one girl, Luna Lovegood, knows that those are thestrals. Only people who have seen death can see those. Harry and Luna are the only two kids on this thing who can see that. So, I loved that metaphor because I saw thestrals really early. When dying is concrete, and it’s someone you played in the sandbox with? I think it becomes very real in a way. I’m sure that’s a central part of it for me.”

Earlier, when we were talking about his book of Twitter affirmations and his fear of being pigeonholed as “inspirational,” Miranda had asked, “What if I want to write a dark dystopian thing next?” It was a rhetorical question. Alas, he’s not working on a dark dystopian musical—this was just something he might do in theory, he said—but I don’t doubt he could create a really grim one if he ever wanted.

Miranda has a brief patter number in Mary Poppins Returns, a kind of music-hall proto-rap, because of course. Otherwise, as Rob Marshall said, “it would be like having Fred Astaire and not having him dance. You need to highlight what someone’s great gifts are.”

Similarly, you don’t interview Lin-Manuel Miranda and not ask about his favorite movie musicals, ones he might be drawing ideas from now that he would soon be directing his own. “In terms of movie scores, I like the old ones the best,” he replied. “I like MGM. I always used to joke that if the last scene of my life was the last scene of The Band Wagon”—Vincente Minnelli’s 1953 backstage musical—“I would have lived a very wonderful life. The scene is Fred Astaire thinks no one’s coming to the opening-night party for his show and he sings, ‘I’ll go my way by myself.’ And he comes out and everyone you’ve seen throughout the movie, everyone he loves, sings, ‘For He’s a Jolly Good Fellow.’ If that’s the last scene of my life, I will have lived a very, very happy life.”

Framing his love of The Band Wagon as his own deathbed huzzah—maybe a better version of “Bye Bye Life”?—seemed quintessentially Mirandian: the cheerleader with a fatalistic streak.

He would in fact get something close to the Astaire treatment when he and other members of the In the Heights cast and creative team appeared for a special event at a Barnes & Noble to celebrate the re-release of the cast album in a 10th-anniversary vinyl box set. Fans had lined up on the sidewalk the previous evening, and half an hour before things were scheduled to start, the store’s event space was jammed with the allotted 500 or so lucky attendees, all wearing wristbands, buzzing and jostling, spilling back into the aisles of books, and singing along lustily as the show’s tunes played on the P.A. system. Most were high-school age or even younger—kids who might have been only six or seven when the Broadway production closed in 2011. Judging from the relatively on-key vocalizing, the theater-geek contingent was well represented. I repeat: this was a promotional event for the vinyl release of a decade-old cast album. How many in attendance even owned a turntable?

Miranda and his colleagues entered to screams and raised phones. Miranda, wearing a newsboy cap, looked sheepish but thrilled. He and the others took their places on a riser and answered questions from an M.C., who eventually opened things up to the audience. The first person to ask a question was a teenage girl, overcome with emotion. “Lin,” she began, drawing a deep breath, and then in a rush: “You are my greatest influence, and when I was alone you were my dearest friend. I was so inspired by your immigrant stories I wrote my own.” She started crying and managed to get out, “I wouldn’t be alive without you—I swear.”

“It’s O.K.!” Miranda said, raising his voice an octave higher—comically, to defuse the emotion, but he was also palpably moved.

Afterward, I went over to the girl, who was there with her aunt. She told me that her name was Fliss, that she was 16, that she was of a mixed Hispanic and Caribbean heritage, and that, at the time she had discovered In the Heights, through the cast album and videos, her life had been in “lots of turmoil.” The aunt nodded sympathetically, encouragingly; “turmoil” clearly encompassed a lot of pain, maybe loss. It felt wrong to probe any further. “I thought my life didn’t have value,” Fliss continued. In the Heights had connected her to her Hispanic roots, had shown her that her own story mattered. “It lifted me up,” she said, speaking confidently, hesitancy and tears gone.

“Who lives, who dies, who tells your story?” as the lyric from Hamilton goes. Maybe Fliss will learn from Miranda the way he took inspiration from Larson. We’ll see. But if this had indeed been the last scene of Miranda’s life, it would have been a pretty good one. Instead, he and his colleagues ended up staying at the store for two more hours, signing albums for a long, snaking line of people who had shelled out $50 for the three-LP set. And not a week after that, he headed off to Wales to start filming His Dark Materials—the flame still lit, the engine still running, the clock still ticking.

Спасибо Вам за инфу. Всех благодарю. Отдельное спасибо пользователю Admin