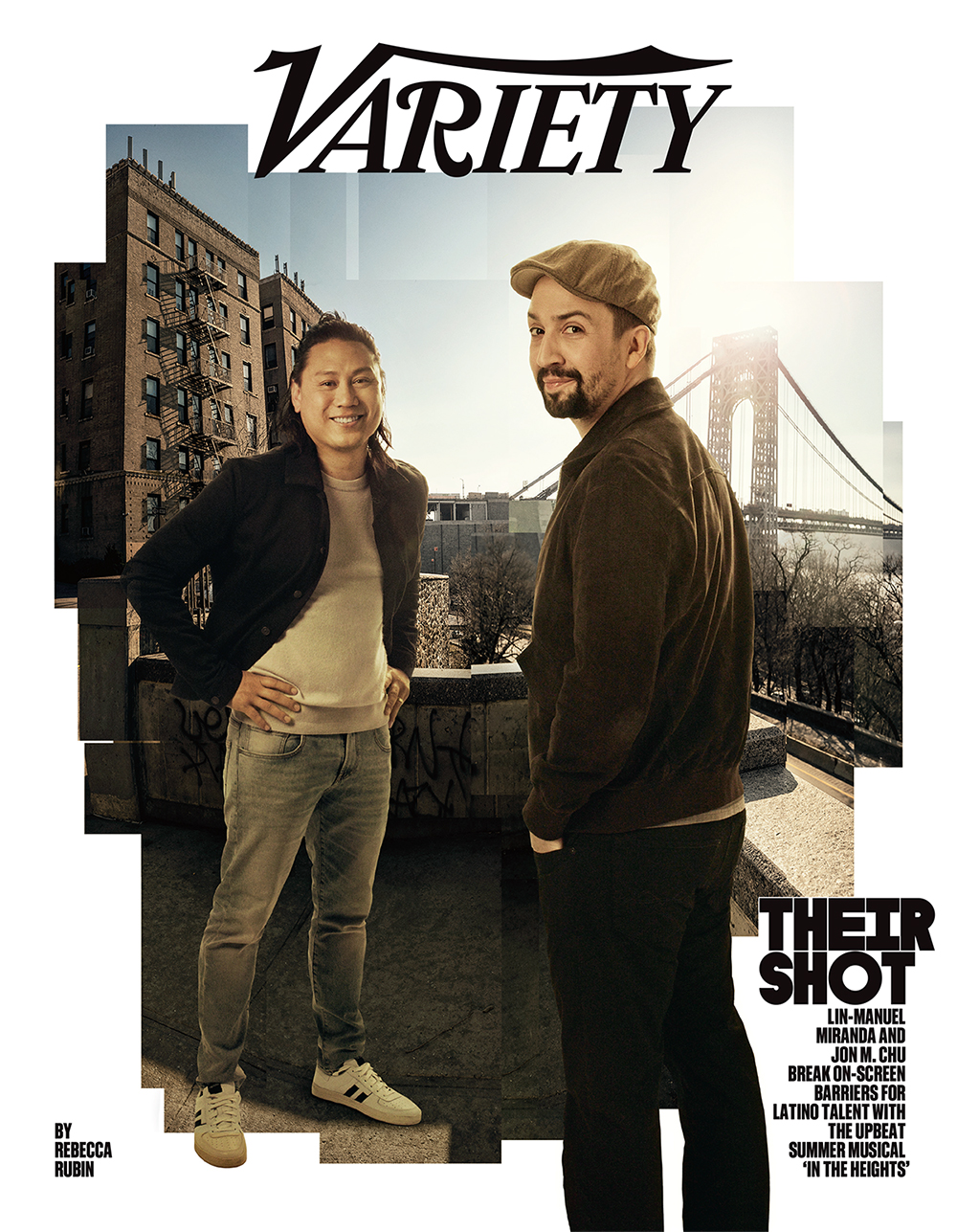

Lin-Manuel Miranda and Jon M. Chu are VARIETY coverstars and the long coverstory includes a lot of voices from In The Heights.

When Lin-Manuel Miranda was pitching his musical In the Heights nearly two decades ago, Broadway heavyweights stumbled over what he was selling. They wanted the young female protagonist Nina, who drops out of Stanford, to have a more dramatic reason for leaving school than the pressures of being the first in her family to go to college.

“I would get pitches from producers who only had ‘West Side Story’ in their cultural memory,” Miranda recalls. “Like, ‘Why isn’t she pregnant? Why isn’t she in a gang? Why isn’t she coming out of an abusive relationship at Stanford?’ Those are all actual things I was pitched.” He pauses for a moment, not to entertain those queries but to consider their absurdity. “Because the pressure of leaving your neighborhood to go to school is fucking enough. I promise. And if it’s not dramatic enough, that’s on us to show you the fucking stakes.”

Miranda stood his ground. The show that he wanted to create emerged from his memories of growing up in New York’s Washington Heights neighborhood and from the painful realization that Broadway roles for Latinos were limited. So he used hip-hop and salsa to pay homage to a close-knit community of immigrants and strivers, bodegas and block parties, friends who feel like family and families that deal with the tensions of trying to make it in the greatest city in the world. In the Heights would eventually open on Broadway in 2008, winning four Tonys and launching Miranda’s career.

Now, that musical is becoming a major summer film directed by Jon M. Chu. The Warner Bros. movie is finally coming out, both in theaters and on the streaming service HBO Max, on June 11. Even after a year’s delay due to the pandemic, the timing couldn’t be better.

And that’s not just because Miranda no longer has to fight to reflect the experiences that have since resonated with countless college students who have felt like Nina. “Because of the specificity of that struggle, I can’t tell you how many people have made it their business to tell me how much it means to them,” Miranda says.

Read the whole story under the cut.

After a hellish year in which audiences have been stuck at home and unable to hug loved ones, In the Heights serves as a joyous snapshot of the life we lost and have been longing to resume. It’s a music-infused love letter to a unique corner of New York City, as well as an unabashed celebration of community and what it means to dream outside the lines. The characters have an uninhibited zest for life, dancing in the streets, across fire escapes and through city parks.

“This is a vaccine for your soul,” says Chu.

But getting to this point wasn’t easy. In the Heights, a movie that Miranda had been trying to make since Obama was elected president, overcame many hurdles and headaches, and was nearly left for dead while its creator struggled to find the right partners to help him realize his vision.

As a studio movie, In the Heights feels revolutionary precisely because its characters aren’t. The story centers on Usnavi (Anthony Ramos), a bodega owner who’s working to save enough money to return home to the Dominican Republic. He’s orbited by an ensemble of vibrant personalities: his childhood friend Nina (Leslie Grace), who “made it out” but fears she will let down her immigrant father as she struggles at school. There’s Benny (Corey Hawkins), a dispatcher employed by the car service owned by Nina’s dad, and one of the only non-Latino characters. And Vanessa (Melissa Barrera), Usnavi’s long- time crush, who dreams of becoming a fashion designer and moving downtown. As in the stage version, their conflicts are grounded in reality and don’t rely on Hollywood’s stereotypical portrayals of Latinos as gang members or drug dealers.

In that respect, the arrival of In the Heights is even more significant. In another era, it might have been marketed as a niche movie rather than a four-quadrant blockbuster. But in the 13 years that it’s taken for the film to get made, Hollywood has undergone a racial reckoning, one that’s challenged long-held ideas about who deserves to be at the center of the frame. It’s a conversation that Miranda and Chu have helped spur — Miranda with his other hit show Hamilton, a once-in-a-generation musical sensation that reimagines the Founding Fathers as a multiracial quartet of freestyling revolutionaries, and Chu with Crazy Rich Asians, a romantic comedy that explodes old prejudices about viewers’ willingness to see a meet-cute with Asian stars.

Yet measuring the success of In the Heights won’t be clear-cut. HBO Max doesn’t provide ratings, and though theatrical box office appears on the mend, it hasn’t recovered from the yearlong pandemic-related closures. That means the film’s final gross could come with an asterisk.

And In the Heights will be the biggest test yet of Miranda’s power as a brand. Will audiences buy tickets based on the promise of catchy tunes and clever turns of phrase from the creative mind behind Hamilton? Or will In the Heights fail to tap into the zeitgeist? Despite the production’s loyal following, movie adaptations of popular Broadway musicals are a mixed bag. For every Chicago or Les Misérables, there’s a string of duds that hit all the wrong notes — just ask the producers of Rent or Cats.

Chu’s career is also at an inflection point. With a range of commercial winners, Crazy Rich Asians, Step Up 2: The Streets and G.I. Joe: Retaliation among them, he’s one of today’s most in-demand directors. But he hasn’t yet become a “name.” If In the Heights is a triumph, it could put Chu in rarefied company. After this film, he’s taking on an even more popular stage-to-screen adaptation with Wicked.

In a conversation over Zoom from opposite coasts — Miranda in New York City and Chu in Los Angeles — it’s clear they aren’t weighed down by expectations, but rather are eager to expend their creative energy to set the stage for a new generation of talent, one that draws on the multiethnic tapestry of America.

“When you are trying to make stories that change what we’ve seen before, you can get caught in the small things,” Chu says. “But you try to do as much as you can, to be as truthful as you can. And the rest, other people are going to fill. We got to crack it open a little bit.”

Warner Bros. is leaning into the show’s inclusive spirit as a major selling point. The studio has partnered with Hispanic and Latino organizations, such as the National Hispanic Media Coalition, to help with outreach and ensure authenticity on-screen. The demographic is routinely the most active among moviegoers. In 2020, Hispanics and Latinos, who represent 18.5% of the U.S. population, accounted for 29% of all tickets sold, according to the Motion Picture Assn. of America — an increase from 25% in 2019. “Latinos have the power to make or break a film, yet we’re only seeing each other in 4% of roles,” says Brenda Victoria Castillo, president and CEO of NHMC.

“How we’re portrayed on-screen is how we’re treated in real life,” Castillo says. “We have a dream to be represented, to be included, in a positive light in Hollywood film. And In the Heights is that film.”

The road to getting cameras rolling could be its own movie, filled with setbacks, false starts and disappointing twists. In the Heights was almost produced at Universal Pictures, which optioned the property after it won the Tony for best musical in 2008, with Kenny Ortega (High School Musical) attached to direct. But the project languished in development purgatory until the studio ultimately dropped it in 2011.

“I was so naive,” Miranda says. “I thought once a studio buys the rights to the movie, the movie’s getting made. I didn’t know the sheer tonnage of miles between acquiring the rights and a green light. You can find interviews of me being like, the In the Heights movie is happening any minute now!”

But Universal wanted a bankable Latino star, reportedly Jennifer Lopez or Shakira. The studio thought it would be too risky to commit a $37 million budget to a musical featuring unknowns and stage actors. “It very quickly became if you don’t have” — Miranda covers his mouth with his hand — “bleep, you’re not getting the money to make the movie.”

It’s that kind of flawed logic, Miranda and Chu argue, that results in a dearth of high-profile movie roles for people of color. “The sentence that rings in my ears from that era is ‘There’s not a lot of Latino stars who test international.’ ‘Test international’ means ‘We’re not taking a chance on an expensive movie with Latino stars,’” Miranda says. “What Jon did so brilliantly with Crazy Rich Asians was he said, ‘These people are stars; you just don’t know who they are yet.’ I think he’s done a similar thing with In the Heights.”

As Universal spun its wheels on In the Heights, Miranda focused his attention elsewhere. He went on vacation, where he picked up a copy of Ron Chernow’s doorstop of a biography of Alexander Hamilton, and the rest is musical history. Hamilton opened on Broadway in 2016 and hasn’t left the cultural conversation since, propelling Miranda into superstardom. That made the movie adaptation of In the Heights a hot property again. Months after Hamilton debuted, The Weinstein Co. boarded In the Heights. But there were more obstacles to come. In 2017, when Harvey Weinstein was in the midst of a massive sexual harassment and abuse scandal, the creative team pushed to get the rights back.

“As a woman, I can no longer do business with the Weinstein Company,” tweeted Quiara Alegría Hudes, who wrote the screenplay and the book for the stage show, in 2017. “In the Heights deserves a fresh start in a studio where I’ll feel safe (as will my actors and collaborators.)”

The filmmakers eventually regained control of the property and began shopping it around. This time, studios were pitching them, not the other way around. And In the Heights felt timelier, given the renewed push for the industry to embrace diversity. Several Hollywood players orchestrated elaborate presentations to woo Miranda and Chu, who was tapped to direct the film in 2016. Warner Bros., for instance, built a bodega on its backlot and re-created poignant touchstones from the screenplay.

“We were not wined and dined. I would say we were piragua-ed a little bit,” says Hudes, referring to the syrupy shaved-ice treats that have a memorable presence in the show. “The studio set up piragua carts and put together their own Weird Al versions of In the Heights numbers with their staff.”

Toby Emmerich, the chairman of Warner Bros. Pictures Group, recalls only a handful of times the studio has gone that far to land a project. “We brought out the old showmanship card,” he says. “It felt like something fresh and new, but it’s a classic story about people and their dreams and losses. It touches on relatable themes for any- one who is human.”

Chu had recently completed production on Crazy Rich Asians at Warner Bros. and made a compelling case to Miranda and Hudes for the level of creative control the studio gave him. Weeks later, they closed the deal and secured a $55 million production budget.

Chu believed that kind of freedom was necessary to find the right cast to bring the bustling city blocks to life. It’s not that charismatic triple threats of Latino descent weren’t out there, but few had been given the opportunity to audition, let alone star in blockbuster movies. However, Chu’s experience in hiring a then-unknown Henry Golding as the hunky heir Nick Young in Crazy Rich Asians only proved his point that resources were needed to expand the hiring pool. Golding has, in turn, used that film as a springboard to land leading roles in the likes of A Simple Favor and Last Christmas.

“[Crazy Rich Asians] gave me the strength in the room to say: We’re going to have to spend more time and money to find the right actors,” Chu says. “You’re not going to find them at an agency. Agencies won’t rep them because there’s no roles for them.”

Miranda, who starred as Usnavi in his 20s, considered reprising the role but felt he had aged out of the part. (He did secure a cameo as a piragua cart owner, a rival of Mister Softee.) So producers embarked on a nationwide casting call. As they were scoping out potential male leads, Miranda attended a 2018 production of In the Heights at the Kennedy Center in D.C. where Anthony Ramos, a member of the original cast of Hamilton, was filling in after the actor playing Usnavi hurt his foot.

The playwright went home that night and, in true Miranda fashion, rhapsodized on Twitter like a proud dad. “I read that shit, and it got me emotional,” Ramos, now 29, says of the social media thread.

But Ramos’ history with Miranda didn’t secure him the part. Though the actor had only a few on-screen credits (his most notable role was in A Star Is Born as the hype man to Lady Gaga’s Ally), Chu was tempted to fill the call sheet with completely undiscovered talent. At Miranda’s urging, he had coffee with Ramos in West Hollywood. The conversation ended with the two sobbing into their breakfast burritos.

“He broke down these lyrics and what it meant to his life,” Chu says. “It broke my heart and gave me so much hope. Oh, and he could sing and dance, he’s charming, and he’s funny and all the things that make a movie star.”

Ramos got another important endorsement from Olga Merediz, who reprises her Tony-nominated stage role as the neighborhood’s beloved matriarch Abuela Claudia. She’s acted against many Usnavis in her three-year stint on Broadway. None, she says, captures the heart of the role like Ramos. “I call him the Puerto Rican James Dean,” she says. “He’s sexy but without trying.”

As weeks passed, Ramos heard nothing. Finally, he got an offer that would conflict with shooting In the Heights. “I texted Jon and said, ‘I just got another job, but I really want to do this movie, bro,’” Ramos recalls. “He was like, ‘Hold. Let me get the suits to move.’ Those were his literal words. And boom, I got the offer the next day.”

Shortly before shooting began in the summer of 2019, Miranda jokingly scrawled, “Don’t fuck this up,” on the corner of Chu’s script. That may have been in jest, but the cast felt the magnitude of the task at hand. It came up with a less profane mantra that Grace, who plays Nina, says she and her co-stars would say to each other on set: “We are our ancestors’ wildest dreams.”

“It made me feel like I had imposter syndrome all the time,” she says. “I was just like, ‘I’m not worthy of this experience.’”

Despite the pressure, the atmosphere was buoyant: The cast bonded over taxing dance rehearsals and strenuous vocal sessions. They were also occasionally greeted by famous friends and family of Miranda’s who stopped by the set, including Anna Wintour and his dad, Luis Miranda.

With more than a decade having passed since the musical debuted on Broadway, Hudes and Miranda felt the need to update storylines with timely references to DACA (Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals), the policy that protects undocumented minors, as well as instances of the microaggressions experienced by people of color. To manage the movie’s run time, they also had to trim beloved characters and songs, even if it meant cutting funny lyrics about the origin of Usnavi’s name (his father was taken by the beauty of a passing U.S. Navy ship).

Lines that hadn’t aged well were also nixed. In the song 96,000, for example, the block finds out that Usnavi’s bodega sold a winning lottery ticket, and overly optimistic buyer Benny dreams about what he would do with the winnings: “I’ll be a businessman richer than Nina’s daddy; Donald Trump and I on the links, and he’s my caddie!” In the movie, he name-checks Tiger Woods instead.

“When I wrote it,” Miranda recalls, “he was an avatar for the Monopoly man. He was just, like, a famous rich person. Then when time moves on and he becomes the stain on American democracy, you change the lyric. Time made a fool of that lyric, and so we changed it.”

Swapping those lines was an easy decision; more difficult was finding innovative ways to make the show cinematic and less stage-bound. When it came to staging 96,000, one of the musical’s flashiest numbers, Chu and Miranda were flummoxed. Inspiration struck on a self-guided tour of the city. They passed the Highbridge Pool, a popular public swimming spot in upper Manhattan. Chu seized on it as the perfect location for a showstopper.

The result is the movie’s most ambitious musical moment, a scene involving elaborate synchronized swimming and dancing that gives Busby Berkeley a run for his money. Capturing the action tested the cast and crew’s resolve. The two June days they shot 96,000 were unusually cold because a storm was brewing, leaving the 500 extras and actors shivering while they waited for Chu to roll camera.

Over the course of the shoot, Chu was often belly-deep in the freezing water, suffering alongside his actors. “I was like, ‘Yo, that’s my director,’” Ramos says. “That’s a dude I look up to. He’s not just in his chair perched up. My man is in the pool. He’s in the fucking mix.”

Right before a particularly arduous bit of choreography involving hundreds of dancers jumping in the air and splashing the water in unison, the cast began clapping and cheering for each other. “It was like electricity,” Ramos says.

It became routine for the cast to experience a cathartic release as Chu would call cut. The director remembers a touching moment during an emotional sequence that transpires in a sweaty, tightly packed alleyway. Miranda was watching from above on a fire escape, and the dancers and singers began to chant his name: Lin! Lin! “He starts to tear up, and everyone starts to tear up because we’re here because of him,” Chu says. “He created this, and now we get to go do other things.”

Months later, when filming was complete, there would be one more wrinkle in the way of audiences getting to see the final product. Chu and Miranda were putting the finishing touches on In the Heights when COVID-19 upended life. Movie theaters across the globe closed, prompting Warner Bros. to postpone the film’s release by a year. Initially, Miranda thought that was a mistake. He lobbied to make it available on a streaming service, believing people needed a reprieve from the pandemic.

“I very publicly was the one person who was really against it,” Miranda says. “I was like, ‘How can we hang onto this for a year when we know how wonderful it is?’”

Chu ultimately convinced him to embrace the delay.

“Jon’s argument to me, which is the correct one, is we can release it now and people would feel good to have it in their homes,” Miranda remembers. “Or we can release it with the right push next year, and then we create a lane of Latinx stars so that I never have to sit in a meeting and hear someone say, ‘Do they test international?’”